Translated by Act for freedom now/”kim”

This book was published in the Autumn of 2011 by comrades who participate in and support the

FUND OF SOLIDARITY AND ECONOMIC SUPPORT OF IMPRISONED FIGHTERS.

(http//tameio.espivblogs.net)

The money from the distribution of this book will be used for the support of the FUND which on a steady and monthly basis covers the material needs of dozens of imprisoned fighters, expressing also in this way our solidarity.We support the imprisoned fighters…

MATERIALLY, ETHICALLY, POLITICALLY

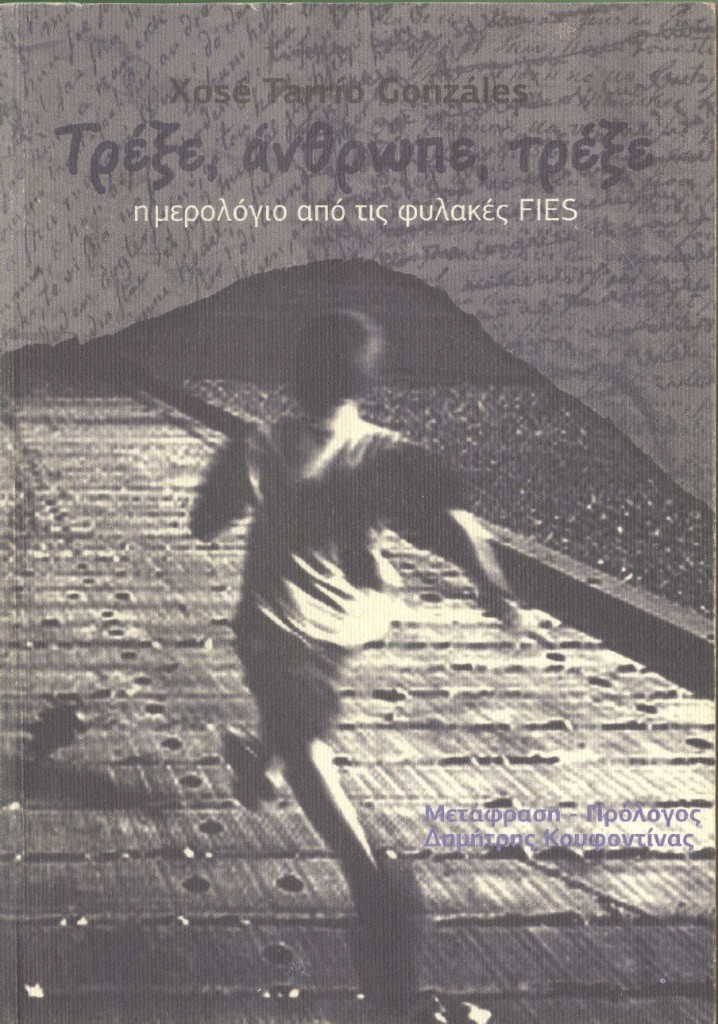

Xosé Tarrío González was born in 1968 in La Coruña of Galicia,Northwest Spain. Poverty and family issues led him to the Institution when he was eleven years old. However his rebellious character could not bear the strict discipline imposed by the authoritarian teachers and nuns who ran the Institution. He escaped twice. At the age of fourteen he entered the world of delinquency. He was arrested twelve times and placed in local reformatories, from where he was always escaping, until they sent him to the central reformatory inMadrid. When he got out of there at the age of seventeen he had already entered the particular world of crime and drugs. In his nineteenth year they arrested him as a fugitive, sentencing him to two years four months and one day imposed in absentia. In the end, he would remain in prison for over seventeen years, spending twelve of them in isolation. They released him, as he himself had foretold, just before his death so as not to become yet another entry in the prison death register. He was 37 years old and his sentence had already reached 71 years. He still had some convictions pending, which according to the proposal of the public prosecution would come to over 100 years.

The itinerary that led Xosé Tarrío to prison is similar to the route of most of the prisoners: poverty, oppression, offences, drugs, reformatory, prison. However, his own journey in life, outside but mainly inside prison, makes him stand out. For his rebellious character; because he did not endure injustice passively; because he kept alive within him the feelings of friendship and solidarity; because his love for freedom guided him continuously to escape; because he did not yield to repression and isolation, did not ‘’escape’’ down the roads that the system itself was pushing him to: drugs, insanity, suicide. And when in the end they threw him into absolute isolation, when all the possibilities of escaping vanished, he turned to books in order to evade. He read a lot, using words, he offered all that he had experienced inside the ‘correctional sewer of society’, as he writes.

Through the pages of this book the reader gets to know the other face ofSpain, the one that is not described in the tourist guides: the geography of legalised pain. The area of institutional violence, with maltreatment, beatings, arbitrariness, abuse of power, censorship, even impeding post; continuous transfers, always further away from the prisoner’s place of residence; humiliation not only of himself but also of his relatives; the treatment of aspirin for patients in severe conditions; gradient isolation to absolute isolation during whole days, months, years until the prisoner breaks down, until they macerate his personality and his resistance; and all this with the consensus and tolerance of the judicial authorities.

The unsuspecting reader reasonably will wonder: how can it happen, how can the most elementary fundamental human rights be infringed in this way? And not even in some far-off era, not in some distant third-world country, not under some dictatorship but rather in today’s democratic Spain, a State of Justice which meets the protocol of the European Convention on Human Rights, and even with Socialist Party PSOE’s governments; which, it should be noted, contributed their best to smarten up the prison image with some window dressing. Some minor improvements were accepted in response to the struggle of the prisoners and solidarity movement; some things were renamed according to the well known Jesuitical way of ”socialists” (Penitentiary Centre instead of prison, employees instead of guards and more); some gaolers insisted on formal courtesy towards the prisoners. However, the substance of the penitentiary monster remained unchanged, and moreover the cruellest scheme of custody: FIES, the status quo of long-term absolute isolation was introduced.

A simple, brief historical overview will confirm that the substance of the prison form remains in principle unalterable, almost regardless of the mode of governance. From the time, historically, that this emerged as a scheme of continuous detention up to this day. During the period when the capitalist mode of production emerges, and in determinist relation to it, as has been explained by the writers of theSchoolofFrankfurt(Rusche/Kirchheimer). The same elementary characteristics distinguish this scheme over time: nutrition always poorer than the lower standard of living of the working class, strict discipline, work worship, continuous control and isolation.

Indeed, prison existed before capitalism made its appearance. But it operated mainly as a space of short-term detention of prisoners or as a method of extermination by starvation or torture. It was needed that a social system appear, one that reduces all forms of wealth into a simple, abstract form of human labour measured by time, in order to assess the infraction (through a commercialized negotiation, as Pashukanis describes the trial) as ”equivalent” to a piece of freedom, and so the deprivation of freedom to be placed at the centre of punitive penalties.

The first form of punitive imprisonment appears of course in the country where capitalism takes its first big steps, Great Britain, around the end of the 16th century. It is the era of impetuous economic growth and a great need for manpower, therefore the offenders, individuals as means of production, must not be ”wasted” and incapacitated with physical punishment but instead be exploited productively. It is also the era where the practice of mass social segregation prevails, through institutions as asylums, sanatoriums, hospices, leper-hospitals and more.

Then, about the end of the 16th century, in England the Work Houses emerge, which quickly spread to all developed capitalist countries; as Tuchthuis in theNetherlands, Casa di Lavoro inItaly, Hôpital Général inFrance, various names inGermany, Switzerland etc. They are the first form of prison, as a place of long-term incarceration where the offender’s labour is methodically exploited and particularly profitable. But also as a practice of social segregation, institutional abduction and integration of marginalized people (beggars, vagabonds, prostitutes and abandoned orphans) to the ”smooth” production process. Moreover, this way the risk of social disorder is eliminated and the most undisciplined people of those strata are preventively neutralized.

Imprisonment in its initial version propagates up to the beginning of the 18th century to the whole capitalist world and constitutes the main instrument of social discipline either indirectly, by correcting the deviant behaviour so that people become more useful in work exploitation, or exemplary by functioning as bugbear, as a constant threat. An important role in the progress of this institution is played by religious rituals which construct a culture of ”appeasement” and persevere the idea, especially through Protestantism, that the sloth is the source of all evil.

Nevertheless, this institution reaches its peak with Bentham’s panoptic discovery. Bentham’s ”Panopticon” (1748-1832) deifies the principle of surveillance. His architectural proposition regards an enclosed space, circular or polygonal, with individual cells that have an open-railed side towards a central point (a tower-head quarters) from where prisoners are continuously monitored, since they are lit twenty-four hours a day.

Even though Bentham’s proposal achieved some savings due to the reduction of security personnel, this is not however just a management plan. The panoptic proposal of continuous surveillance (principle of control) is completed by the principle of isolation, in various gradations (complete isolation, interruption of isolation only during the hours of common labour in silence, etc.) and constitutes the substance of the capitalist form of prison. Iñaki Rivera considers that the real significance of panoptism is the construction of an ”exterior space”, different from the legal diagram where ”a strength could be tested detached from the official limits of the Social Contract which are imposed by the political society”, where a new pedagogy of dependence of human upon human can be applicable.

This form of imprisonment discovered during Enlightenment (Foucault said ”the Enlightenment which discovered the liberties, also invented the disciplines”) formed its final figure from positivism. Positivists, mainly the Italians LaBruzzo, Garofalo and Ferri analyze offenders’ personalities in order to find a ”scientific” explanation of delinquency. The first is looking mostly for biological factors, the second one the psychological and the third one the social ones. Yet, the current that they represent insinuates, as Bergalli emphasizes, a pathological base of offenders. From the perspective that we are discuss this issue here, we are interested in their statement, the ”progressive” imprisonment scheme. Progressive is in the sense of a gradual swing from absolute isolation to work under more flexible conditions of detention, even to conditional release. The criterion for this gradual change in conditions of detention is the degree of ”reform” and intends to ”reinstate the person as obedient and useful”, as Foucault describes.

Thus, the contemporary form of prison is completed, with the combination of panoptic isolation and constant surveillance, disciplinary measures of the legal institutions and psychological behaviourism, continuous evaluation of the behaviour of the detainee, rewarding rehabilitation from ”deviation” and punishing insubordination and disobedience.

Xosé Tarrío González had met with this ”progressive” prison scheme and he described it so shockingly. It was applied inSpainby LOGP, General Penitentiary Law, which noted it was the first (!) Act of Constitutional Development to be voted during the Spanish political changeover, and established three degrees of detention: in the first degree, ”closed’ custody, prisoners remain locked in cells for 23 hours a day (characterized as ”bitter necessity” by its introducer, with the well known sad look that Democratics and Socialists have when announcing brutal measures). In the second degree, ”common” custody, prisoners are working and can take leave of up to 36 days a year. In the third degree, ”open” custody, prisoners can work in morning shifts outside prison. In the end, conditional release is established.

The socialist government inSpainhad the honour of completing this ”progressive” system by introducing what is called ”modern culture of emergency measures”. (InGreece, the progressive professors have had the equivalent honour, as they suggested the anti-terror laws and also the modernized government that introduced the special conditions of detention, as well as the high-security prisons). Then another degree of custody was created, that of long-term absolute isolation for the FIES prisoners (on special surveillance), the cruellest and most cold-blooded mode of custody, the one that so many prisoners like Xosé Tarrío had experienced, the one that killed so many prisoners by pushing them to insanity, to suicide. The very same, noted, is still valid and applicable and keeps torturing the prisoners inSpaineven today.

Xosé Tarrío González faded at his 37 years. ‘”He died of prison” his mother will say, concentrating, with all the wisdom, so much truth, so much pain, so much anger, in this short sentence. This book was his way to breathe in the suffocating world of prison. It is his scream, his struggle to comprehend the organization and functioning of the penitentiary monster, but also the social structure that it comes from. ”The system forces you to be a part of it under the threat of imprisonment, and once you are imprisoned, under the threat of punishment”, the author will briefly describe prisons, this last fortress of the present politico-economic plan. This book is a slap to those who consider imprisonment as something distant, to those who end their sensitivity in front of the prison walls, to those who with their silence and tolerance legitimize prison. This book contributes to the formation of critical consciousness, to the development of cultural resistance, to the understanding that the struggle against prisons is an integral part of the struggle for social liberation.

Δημήτρης Κουφοντίνας

* Dimitris Koufontinas, member of 17 November Revolutionary Organisation serving three life sentences in the special wing of Koridallos prison,Athens.

Notes: the following books are sources from which information and data about the history of the prison institution, the penitentiary system in Spain, the particular conditions in Spanish prisons, the struggles of the prisoners but also of the solidarity movement, as well as for the author himself, have being gathered: Κ. Φλώρος ‘’ Οι άνθρωποι που κύκλωσαν το άλφα’’ (The people who encircled alpha) 1704621 editions, Athens 2010 * Ν. Κουράκης (editor: Ν. Κουλούρης) ‘’ Ποινική Καταστολή’’ (Criminal Repression) Σάκκουλας editions, Athens-Kommotini 1997 * leaflets: Dossier Agustín Rueda, Dossier Anticarcelario, Barcelona * texts: by Iñaki Rivera, professor in the University of Barcelona and by Gabriel Pombo da Silva, prisoner in Barcelona and in Germany, comrade of Xosé Tarrío for the Spanish and German edition of the book respectively. Priceless was the help offered by the comrades, both during the translation process and the typing (and often decryption…) of the manuscript, the repetitive corrections, the setup of the book and finally the printing, showing this commitment of words and deeds that gives substance to the concept of solidarity.

http://actforfree.nostate.net/?p=10435#more-10435