On 11 April 2012 the Indonesian parliament ratified a law on managing social conflict (Penanganan Konflik Sosial – PKS) in order to address Indonesia’s experience of dealing with social conflicts, which has often been considered less than perfect.

The government had previously used a range of different existing regulations as its reference when dealing with conflicts. However they felt that this produced difficulties for subduing conflicts that spring up among the population. The government also felt the need for a single legal reference point to handle such cases. When dense conflicts with ethnic, religious, racial or intergroup aspects occur, such as happened in Poso (Central Sulawesi) or Ambon, the state’s response is perceived as slow and less-than-optimal because the government finds it difficult to formulate the appropriate steps to take, as the procedures for dealing with social conflicts are unclear.

But is the main reason for this new law really just to bring about peace and restrain conflict? Or were there other more fundamental and strategic objectives that needed addressing – ones that would serve to benefit certain other interested parties?

Agrarian Conflict in the PKS law.

The first clause of the PKS law defines social conflict as “clashes involving physical violence between two or more groups or factions that results in dispute and/or fatalities, loss of property, has a widespread impact, and occurs within a specific time-frame whereby instability and social disintegration emerge, potentially hampering national development in the sense of achieving security for society”. This definition is clearly extremely broad and could be interpreted in many different ways depending on how the conflict is viewed. This therefore gives a grand scope to the government to act against all forms of “social disorder” including agrarian conflicts which make up the greatest number of horizontal conflicts occurring in Indonesia. The Consortium for Agrarian Reform ( Konsorsium Pembaruan Agraria) has noted that in 2011 there were 163 agrarian conflicts, 22 farmers or others were killed and more than 120 people were injured by gunshots. 69,975 families were affected by these conflicts, with the total land area under contention stretching to 472,048.44 hectares.

According to the letter of the law, it exists for conflict deterrence, management and recovery within the conflict area, with the local (provincial or regency/city) government authorised to mobilise the armed forces. A connection can be drawn here with the handling of agrarian conflicts in which local people (farmers or fisherfolk) are often involved in a dispute with companies or corporations. In such conflicts the corporations always want to resolve their problems in the easiest and cheapest way to make sure they don’t lose out. That is why companies often follow the same pattern in dealing with land disputes. They incite horizontal conflicts that pit one group of people against another so that the company can easily take control of the land.

This model works by bribing the elite or local leaders, only offering some of the people compensation for their land or employing some local people who can be easily enticed by high wages and then end up siding with the company. In some situations, physical fights between the people cannot be avoided and property or lives are lost, eventually clearing a way for the company to establish control over the land. Under such conditions agrarian conflicts change into conflicts between the people and that can become a strong reason for the government to intervene to put an end to the conflict, resulting in the company’s victory in the land dispute.

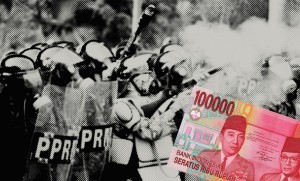

Repression of Social Struggles

The PKS law makes clear that the government can at its discretion deploy national troops with battle capabilities that exceed those of the police. This law opens a wide space for heavy militaristic repression just like often happened during the 32 years Suharto was in power. It is also easy for the state to stigmatise social struggles in which people are demanding their rights, or indeed desiring a more complete social transformation, as a social conflict that must be restrained and extinguished. Just as the state keeps coming out with the same tired old values of stability, calm and order, this law claims that it can bring about such things by pushing for development and economic growth to increase security amongst the people. However, such clichéd phrases are used to obscure the true condition of society, where expropriation, exploitation and insults dominate Indonesian people’s daily lives. When the government speaks of creating calm conditions, what it really means is a situation that is conducive for big companies to seize people’s land and destroy people’s economic autonomy, forcing them into waged labour.

To smooth the way for companies to multiply their profits, it is vital they find the right way to prevent resistance from emerging and spreading. If the government’s attempts at persuasion, often involving NGOs as agents of social moderation, should fail, mobilising the forces of the military becomes the next choice to repress the people, under the pretext of securing and stabilising the situation. This becomes easier to do under the new law with the decentralisation of the power to establish an area as one of “social conflict”. In fact, with the practice of regional autonomy local governments often become loyal guards of companies’ interests. The cases of Morowali, Bima, Mesuji, Takalar and Semunying are proof that government is an important player in ensuring a smooth way forward for mining and plantation companies’ operations, ensuring permissions are swiftly given without the need to let local people know, and even taking the lead in preventing the people from doing anything about it. We can conclude from this that this new law will tend to reinforce the power of local governments, which have always taken it upon themselves to weaken each individual within their territories, spreading ignorance and using the law and forces of order to repress people, in order to be able to control them more easily and so continue doing exactly what they want.

In the case of social conflicts which at least on the surface are reported as being related to ethnicity, religion, race or intergroup factors, we can learn from the history of human civilization where a way can always be found to resolve such conflicts that fits with the local culture. Societies that have not experienced a formal system of government can always find some balance within their surroundings, even though war is often not avoided. Connected with this, the new law also assigns customary law (adat) bodies and the Conflict Resolution Commission (KPKS) as the institutions which should set in motion peace and reconciliation processes between conflicting parties.

Attempts to react to conflict clearly require substantial amounts of money, especially if the conflict should escalate. As a solution to the state’s incapacity to resolve conflict, it uses this law to empower local agents to achieve a resolution. Forums such as the musyawarah mechanism that have their roots in local cultures are appropriated and institutionalised in the interests of stability. But when the state takes over the people’s forums like this, anger can easily spread. In both the organisations relating to adat and the KPKS, state elements are very dominant, so the dialogue process will tend to avoid resolving the root causes of the problem and push the people to continue to obey the regulations as enacted by the government. In certain circumstances this is a cheap and easy way to dampen the fire.

Remembering that all laws and regulations are made by a handful of people in privileged positions with their own interests over our lives, we should always be cautious. The domination of a few over the lives of the rest must be stopped. Don’t wait around, get started now!