Biographical/historical notes:

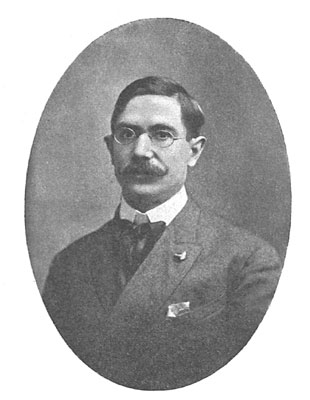

| Giuseppe Ciancabilla was one of the important figures of the anarchist movement who immigrated to the US in the late 1800s, along with F. Saverio Merlino, Pietro Gori, Errico Malatesta, Carlo Tresca, & Luigi Galleani. According to historian Paul Avrich, Ciancabilla was one of the most impressive (now one of the least well known) of the anarchist speakers & writers. Giuseppe Ciancabilla was born in Rome & moved to America in 1898 & settled in Paterson, New Jersey, a major stronghold of Italian anarchism. He became the editor of La Questione Sociale (The Social Question), a paper which Pietro Gori helped establish in 1895, & one of the leading organs of Italian anarchism in the US. Ciancabilla eventually moved westward, settling among the Italian miners of Spring Valley, Illinois. After the assassination of President McKinley in 1901, the anarchist groups were raided by the police, & Ciancabilla was driven from pillar to post, arrested, manhandled, & evicted. Driven out of Spring Valley, driven in turn out of Chicago, Ciancabilla wound up in San Francisco, editing the journal La Protesta Umana when he suddenly took ill & died in 1904 at the age of 32, one of the most intelligent & capable of the Italian anarchists in America. http://recollectionbooks.com/bleed/Encyclopedia/SaccoVanzetti/essaypa.html

The following text is from “Willful Disobedience” (Volume 4, number 3-4, Fall-Winter 2003): Giuseppe Ciancabilla was born in 1872 in Rome and died at just 32 years old in a hospital in San Francisco, California. At the age of 18, he went to Greece to join in the battle against Turkish oppression there. He acted as a correspondent for the Italian socialist paper, Avanti!, but rather than fighting with the Italian volunteers he joined a group of libertarian combatants from Cyprian Amalcare who sought to encourage a popular insurrection through partisan guerrilla war. In October 1897, he met Malatesta to do interview for Avanti!. This meeting and the response of the PSI (Italian Socialist Party) leadership to the discussion led Ciancabilla to leave the socialist party in disgust and declare himself an anarchist. This “Declaration” appeared in Malatesta’s paper, “L’Agitazione” on November 4, 1897. The choice of becoming an anarchist forced Ciacabilla and his companion, Ersilia Cavedagni, to flee Italy. After a short time in Switzerland and Brussels, Ciancabilla moved to France where he collaborated with Jean Grave on the paper, Les Temps Nouveaux, though the editors felt the need to occasionally point out their differences with his perspectives. In 1898, when the Italian authorities pointed him out as a “dangerous anarchist”, Ciancabilla was expelled from France. He returned to Switzerland where he attempted to bring together Italian revolutionary refugees. He was expelled from Switzerland for writing the article “A Strike of the file” in defense of Luigi Luccheni [he stabbed the Empress Elizabeth of Austria —ed.] for the anarchist-communist paper “L’Agitatore” that he had started himself in Neuchatel. After a short time in England, he decided to move to the United States. Once in the US, he was called to Patterson, New Jersey to direct the anarchist paper “La Questione Sociale.” However, due to changes in his ideas, he quickly found himself in conflict with the editorial group of the paper who supported Malatesta’s organizational ideas and methods. In August 1899, Malatesta came to the US and was entrusted with directing “La Questione Sociale.” This led Ciancabilla and other collaborators to leave that magazine and to start the journal “L’Aurora” in West Hoboken. Besides spreading anarchist ideas and propaganda in “L’Aurora,” Ciancabilla used it for translation including works by Grave and Kropotkin. His Italian translation of Kropotkin’s The Conquest of Bread even managed to make its way into Italy despite legal hardships. The final period of Ciancabilla’s life was spent between Chicago and San Francisco where he published the journal, “Protesta Umana,” a review of anarchist thought. Ciancabilla was always explicit about being an anarchist-communist, but was equally explicit (like Luigi Galleani, another Italian anarchist immigrant active in the US at that time) about his critique of formal organization and his support for those who took individual action against the masters of this world such as Michele Angiolillo, Gaetano Bresci and Leon Czolgosz [who shot American president McKinley — ed.]. On September 15, 1904, he died, attended by his companion. The following article briefly expresses his ideas on organization.

|

http://www.reocities.com/kk_abacus/vb/wdv4n3-4.html#ciancabilla

FIRED BY THE IDEAL by Giuseppe Ciancabilla

Introduction

On the 6 september 1901 Leon Czolgosz shot and badly wounded President William Mckinley at the Pan American Exposition in Buffalo. McKinley would die from a gangrenous infection eight days later. Arrested at the scene Czolgosz was quickly interrogated. He implied that was an anarchist and suggested that had been influenced by Emma Goldman and another woman radical he did not name (Czolgosz had heard Goldman speak in Cleveland on 5th May, 1901 and had spoken briefly with her another time in Chicago rail station when she was saying goodby to some of the anarchists around Free Society). He did make it clear however that he was not part of a conspiracy including Goldman and anyone else.

Immediately after he signed his statement (at:10:20pm that evening) Secret Service officers in Buffalo sent a telegram to the Chicago police asking them to find and investigate the location of the headquarters of Free Society, the anarchist communist paper. Subsequently Abe Isaak (the editor), Abe Isaak jnr, Hippolyte Havel (future editor of Revolt, Road To Freedom and,, for a time, Man), Enrico Travaglio (future editor of La Protesta Humana, The Petrel, Why and the Dawn), Clemens Pfeutzner, Julia Mechanic (later present at the founding conference of the industrial Workers of the World in June, 1905), Marie Isaak, Marie Isaak jnr and Alfred Schneider were arrested and charged with being implicated in the plot to assassinate President McKinley. The men were subjected to all night interrogations and held without bail; the woman were released a few days later.

A vicious press campaign vilifying Emma Goldman began. Portrayed as the “High Priestless of Anarchy” (Chicago Tribune, September 8, 1901) effigies of the were publicly hung in a least two cities. Goldman had heard about the assassination attempt when working in St. Louis and quicly moved incognito to Chicago to help her arrested comrades. Arrested there on the 10th September and released on 24th September. Like the anarchists around Free Society released the previous day no charges were made agaist her.

Other anarchists were attacked or arrested as a result of the attack on McKinley. Johann Most was arrested for reprinting in Freiheit and old article by Karl Heinzen (written in 1849) on political violence as space filler….hours before the shooting. Most would eventually serve ten months in prison for it.

The office of the Yiddish anarchist paper Freie Arbeiter Stimme was attacked on the 15th September. Anarchist in Home Colony, Tacoma were threatened and, on the 16th September the widow of Gaetano Bresci, anarchist assassin of Italian King Umberto in 1900, was ordered to leave Cliffside Park, New Jersey. Bresci had been found dead in his prison cell on 22nd May 1901.

Another anarchist who suffered attack was Giuseppe Ciancabilla (1872-1904). Arriving in America in 1898 he edited La Questione Sociale in Paterson (1899) and at the time of McKinley’s assassination was editing the uncompromising L’Aurora in West Hoboken. Running from 1899-1901 the paper was based among the Italian miners of Spring Valley, Illinois but reached out to Italian militants throughout America. The paper, as our selections show, offered a profound political and moral support for the action of Czolgosz is a “giant among men”. No matter that the state is “democratic “ and the killing could lead to a “state of reaction”. Is the bourgeoisie likely to grant us a truce?

The anarchist group in Spring Valley were raided by the police, Ciancabilla was arrested and finally evicted. He went to Chicago, then to San Francisco where died of consumption in 1904. At the time of his death he was editing La Protesta Umana.

Leon Czolgsz, was electrocuted to death early in the morning of 29th October 1901 in Auburn prison, New York.

Giuseppe Ciancabilla: A Look at Italian-American Anarchism at the Beginning of the 20th Century by Mario Mapelli.

Although covering a limited time-span, 1898 to 1904, Giuseppe Ciancabilla’s political experience provides us with a change to retrace one of the countless ideological threads generally all lumped together under the broad umbrella of “anarchist individualism”. In fact it was Pier Carlo Masini who described Giuseppe Ciancabilla as the man who first equipped Italian anarchist individualism with a serious theoretical profile. Furthemore, as Ciancabilla’s though came to its complete maturation and definition in the setting of the Italian anarchist emigre’ community in the United States, in retracing his personal history in my research work, I have tried to reconstruct the difficulties and limits within which the early 20th century Italian-American anarchist community operated and understand why in might have fertile soil for the propagation of the anti-organisational ideas peddled by this Roman anarchist.

The ideological foundations of his anti-organisational anarcho-communism were conceived by Giuseppe Ciancabilla during his stay in France in 1898 and through contact with the group around Les Temps Nouveaux. The French anarchist elite of the day was heavily influenced by Kropotkin’s theories and, especially where the movement’s rank and file were concerned, there was still the fascination with the “heroic age”, of attentats, highlighted also by some exponents of the artistic and literary avant-garde of the day.. Ciancabilla, a recent convert to anarchism after a career in the ranks of the socialist youth in the Italian capital and first-hand experience as a volunteer in the Greco-Turkish war, distanced himself (whole on French soil) from the federalist theory of Malatesta of which he had backlash that came in the wake of the bread riots in Italy), he stressed the demolitionist side of anarchist action and came up with a spontaneist notion of revolution, in the shape of the unfettered action of tiny nuclei, in which “propaganda by deed” retained a fundamental importance.

Ciancabilla’s anarchist outlook was only fully formulated in his polemic with Malatesta and the Gruppo Diritto dell’Esistenza of Paterson, New Jersey, which, precisely because of ideological differences and capitalising upon the arrival of the anarchist leader (Malatesta) stripped him of the directorship of La Questione Sociale in September 1899. However, even during the first foray into publishing in which he had played a central part, with L’Agitatore of Neuchatel, Ciancabilla had had occasion to set out stance on individual attentats from which he never departed. Faced with Luccheni’s attack themselves from it, questioning the point of an act that struck at someone who had long had little to do with the palaces of the mighty. Ciancabilla, by contrat, put his signature to an article eulogising the assassin and arguing that it was up to anarchists to claim any act of rupture with established order, regardless of the usefulness of the act.

In the United States this young Roman fitted into the climate of the various Italian anarchist groups which had begun to emerge during the final decade of the 19th century. Italian emigration to the United States was just then beginning to experience crucial growth, but the real boomtime came between the latter half of the first decade of the 20th century and the First World war. The workers who were arriving were, for the most part, lacking in experience of class organisation and, in the case of those few who had embarked upon political activity back in the old country, his had been confined to brushes with the law, given that the reactionary climate in late 19th century Italy had generally put paid to any real, day to day propaganda work inside the trade union organisations which were just starting to expand at the time.

Across the Atlantic anarchist propaganda encountered its greatest obstacles in the ignorance of the émigrés and in the role played “bigwigs” who offered themselves as go-betweens between the ethnic community and American reality and whose dominant position was itself a guarantee that the émigrés cultural deficit would persist. In the context, the anarchist groups represented a “colony within the colony” and much of their activity was devoted to protect the ideological inheritance and anarchist tradition which were the touchstones around which the various groups could rally, rendering any organisational super-structure (which the uncertain circumstances of the workers themselves made difficult) redundant. So it was only natural that tactically the preference was for revolutionary action free from any programmatic ties and founded upon forms of inter-individual understandings geared to specific propaganda purposes. The range of values advocated by anarchists (anti-clericalism, anti-patriotism, free love) offered a “world turned upside down” that often struck a certain fear into the rest of the Italian émigré community. So it was easier to be open to contacts with other immigrants groups, especially “the Latins”, but within the parameters of the anarchist world with its shared traditions and ideologies than to draw in other the other un-policised Italian workers who were primarily reached through the countless recreational ventures which every anarchist groups relentlessly advanced.

At the same time, American society, imbued with xenophobic feelings for these “new immigrants, was hostile to the Italian immigrants and much more so to those politicisied groups which, it was believed, brought with them incendiary theories of class violence foreigh to the democratic traditions of the Republic. The native anarchist tradition, whose leading exponent at the time was Benjamin Tucker, was bound up with a pacifist individualist outlook that immigrants anarchist found quite considerable problems cooperating with. Furthermore, the American thade unions, headed by the American Federation of Labor, had hopted for a business unionism that ruled out any prospect of radical change to the relations of production and restrincted its attentionsd to unionism “pure and simple”. Thus they busied themselves organising the respectable segment of the American working class, to wit, the skilled white work force with the longest tradition of organisation, excluding the new unskilled immigrants who were the unwilling protagonists of the business restructuring process and who looked like undermining the power at the skilled work force in terms of the sped and character of the process of production. In this respect the American trade union organisation with their corporative policy and hgh membership dues kept the Italian workers at arm’s lengh and reproduced within their own ranks the ethnic differences that could also be found in the factory hierarchy context. In view of which the Italian-American anarchists challenged the moderate line of the American unions as well as their centralised and bureaucratic structures and tried to make hay out of occasional outbreaks of immigrant rebelliousness which the violence of the relations of production made inevitable and they aimed to turn up the heat as high as they could on class conflict.

Against this backdrop, Giuseppe Ciancabilla’s propaganda –appealing to the generic values of “anarchist purity” and rejecting compromise in any form, whether with groups outside the anarchist community or within the framework of US trade unions – directly addressed the situation in which Italian anarchist militants had to operate in the United States at the beginning of the 20th century. In addiction, his talents as a publicist and his many contacts in Europe allowed his newspaper,operating as a sort of international sounding-board, to seize upon the stimuli and fresh theoretical musings being hatched by the anarchist movement internationally, albeit whilst confining these within the limits of a spontaneist vision of revolution. In this regard his work was important as a vehicle for the communication of new tactics and theories which became the inheritance od subsequent struggles as experienced by the American Working Class. It should be noted, for instance, that, on the back of the enthusiasm aroused by the initial successes of the French anarchists: commitment to the labour movement, Ciancabilla launched a campaign in the United Staes in favour of the revolutionary general strike.

Indeed Ciancabilla persisted in rejecting any methodical work within the workers’ organisations and declared that his efforts should be geared aoly towards “creating the mind-set” for the general strike, which was nothing more than the transference on the terrain of the relations of production of the traditional, insurrectionist, voluntarist conception to which much of anarchism had been subscribing since its inception. Yes the series of pamphlets and contributions from French syndicalism’s leading exponents on offer from his newspaper and available to militants in their meeting halls and in the labraries set up by the various groups allowed ideas to circulate and represented a significant ideological baggage for Italian immigrants into the United States.

The verbal violence with which Ciancabilla’s newspaper were riddled fed this vindictive feeling that many immigrants forced into emigration in order to flee poverty or escape problems with the law, were to feel towards the homeland that had rejected them. It is no coincidence that it was from the Italian-American community that Gaetano Bresci set off on his mission and that his name is listed among the subscribers to L’Aurora, one of Ciancabilla’’s papers.

The backward glance at Italy which appeare to offer better prospects of revolutionary developments than the United States of the early 20th century. Through ongoing contacts, the anti-organisational inclinations of Italian-American anarchism continued to exercise significant influence over the anarchist movement back home. Ciancabilla was personally involved in the furious arguments which at that time divided the organisationist Italian anarchist around Il Pensiero, the paper of Gori and Fabbri, from the anti-organisationists around Milan’s Il Grido della Folla. In the latter newspaper the first article were starting to appear wherein an unmistakable Stirnerite and Nietzschean influence was discernible. It has to be said, however, that Ciancabilla’s anti-organisationist anarchism essentially kept its distance from the exasperated anti-social egoism, the first symptoms of which had begun to emerge in some of the exponents of early 20th century Italian anarchism. Common ground could be found with Stirnerite currents, however, in a shared opposition to the “lullaby” anarchism of Gori and Fabbri and in the readness to lay claim to any act of revolt against the burgeois order. This had always been part of Ciancabilla’s ideological inheritance.

(Bollettino Archivio G. Pinelli, n. 114, December 1999, pp.9-12) for more information on Ciancabilla see Ugo Fedeli, Giuseppe Ciancabilla (Imola, Galeoti, 1965)

–extract from;”Fired by the Ideal” by Giuseppe Ciancabilla, Kate Sharpley Library, translated from the Italian by Paul Sharkey. First English edition published by the Kate Sharpley Library, 2002, re-printed 2007.